A common conversational trope you may have encountered is where a person asks friends: “what is the deadliest animal in the world?” After some thought they may respond with mosquitoes or sharks but then they will be met with the answer of “humans”. This witty, intellectually superficial thought makes for a good conversation piece, but it isn’t exactly true. Yes, humans do hold the number two spot considering the rate of which we desecrate and abhor the natural world, but in terms of sheer number, the bacteriophage holds the crown. Bacteriophages, or more commonly known as phages are viruses that are potent for bacteria and they are found essentially everywhere. They are the most common genetic entity on earth outnumbering all others about ten to one. This makes sense once you consider that phages are found where their food is (which is bacteria) and bacteria are everywhere as well. These viruses are merciless in their destruction of the bacteria they are suited to kill. They inject their DNA into the bacteria of choice, once inside the bacteria begins inadvertently producing more phages until the pressure causes the bacteria to burst and die, releasing all the new phages. Hearing of the omnipresence and efficiency of this serial killer they may sound a little off putting however phages have the potential to bring about the second revolution of fighting our modern-day super-bug bacteria.

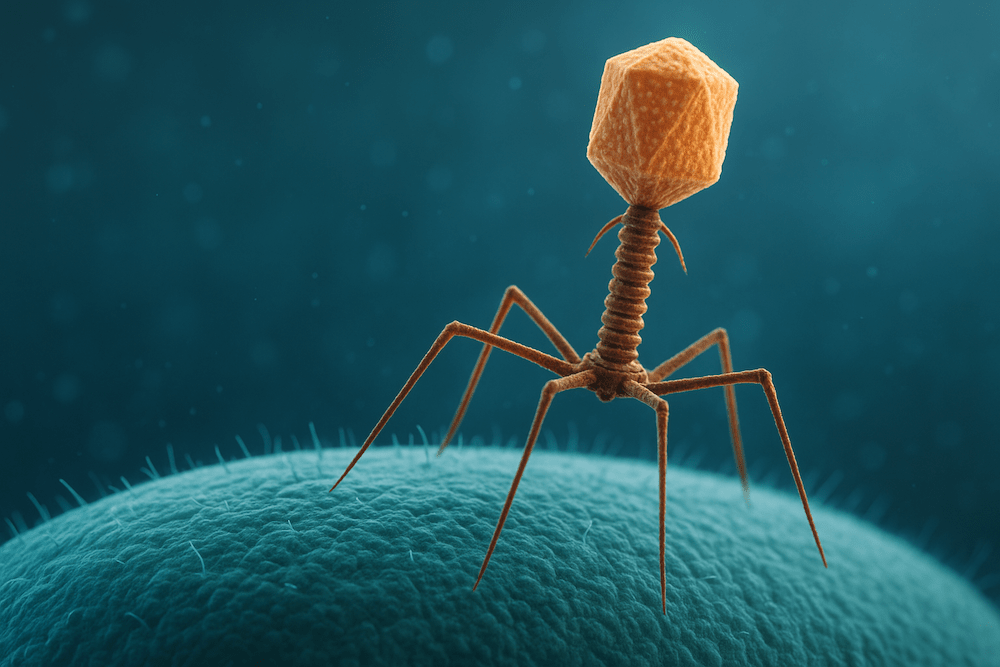

Felix d’Herelle, a French microbiologist was the one to discover these phages. The very first hints of the virus occurred in 1896 when scientists noticed that the Ganges River contained something in the waters that had anti-bacterial qualities against Cholera. Later in 1915 Bacteriologist Frederick Twort discovered a substance that infected and killed bacteria. Twort had a few ideas as to why this had occurred wether it was an enzyme produced by the bacteria itself, if it was a bacteria destroying virus or a stage in the life cycle of bacteria. Twort couldn’t reach a conclusion as his research was prematurely cut off due to World War I. Two years later in Paris, d’Herelle observed that there were clear spots on bacterial cultures indicating where bacteria were being destroyed and claimed he had discovered “a virus parasitic on bacteria”. It was d’Herelle that coined the term bacteriophage, deriving from the Greek phagein, meaning to devour. d’Herelle conducted his first real tests in the United States in 1922 which paved the way for future research and progress although the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, put phage research on the back foot for essentially the rest of the 20th century. D’Herelle wouldn’t have seen any phages himself but rather the biological footsteps through the remains of its prey. With highly sophisticated equipment, unavailable to d’Herelle, a person would observe a virus with an icosahedral (20 sided) protein head containing the genome and a tail with which it injects its host. Although this is the basic structure, phages can vary hugely in their design and specialised functions. When a phage comes across a bacterium, it attaches itself with the tail, injecting its genetic information into the bacteria. This hijacks the bacteria and prevents the bacteria from producing bacterial components but instead forces the bacteria to produce viral components, mistaking it for its own DNA. Eventually, as the new bacteriophages are assembled and the pressure builds, the bacteria burst and expose the new phages to the outside in a process known as lysis.

Félix d’Herelle

The question that now remains is how does a bacteria killing virus have any importance for humans?

Well one must imagine this as an enemy of my enemy is my friend situation. We modern humans are fortunate enough to not have to consider bacteria as a deadly threat due to the wonders of penicillin and subsequent antibiotics. However, there was a time not that long ago where a thorn prick could kill a person and the reason being bacteria. In modern times we simply brush away even the mildest ailments caused by bacteria with some antibiotics from the local pharmacy, but the global implications of this as a sustained and normalised practice are bleak to put it lightly. The more antibiotics that are taken the more bacteria are killed but it also means that the bacteria that survive and are immune to antibiotics can grow and strengthen, these resistant superbugs potentially rendering antibiotics useless. We can reduce the effects by ensuring we do not misuse antibiotics, we finish full courses and reduce use in rearing livestock and food growth (which shockingly is where 70% of antibiotic use arises) however in reality humans are consumptive and impulsive creatures. This low underlying use of antibiotics in our bodies allows bacteria to grow and learn how to cope with antibiotics and so this development of these super bugs extrapolated onto a global scale displays the urgency of this problem and so in order to avoid some reports that project 39 million deaths between 2025 and 2050 phage research development is a necessity. Phages offer so much in way of effective treatment against bacteria. Instead of carpet-bombing methods of antibiotics, phages target specific strains or bacteria and can be prescribed effectively to avoid destruction of beneficial bacteria. Another factor is wether bacteria won’t just evolve and overcome bacteriophages in the same way they evolve around antibiotics? Unlike antibiotics, phages can evolve along side their rival bacteria, creating a biological arms race lasting billions of years where bacteria cannot out-evolve their predators. However, phages aren’t perfect either, Doctors must carefully select the most appropriate phage, and regulation is a much more tedious task as phages are evolving biological units which are much harder to legislate than fixed chemicals.

Despite these limitations, there has been an ever increasing use of phage therapy in medical practice globally. However, if we are to ensure definitive results and long-term prevention of bacteria driven disease, both phage therapy and antibiotics should be used in conjunction in the tool kit of hospitals. Evidence suggests that bacteria that become more resistant to the attack of phages, simultaneously lose resistant to antibiotics. Creating an attack of two fronts, pinning the bacteria in a corner. Bacteriophage usage is still rare and difficult to legislate in medical practice with big Pharma and health organisations. But knowing that the development of phage therapy can offer an effective treatment to what the W.H.O expects to be one of the greatest threats to human lives in the next 25 years is surely enough justification for advancing research and use of phage therapy. As the age of antibiotics is drawing to a close and the super bug era dominates global health, more progressive and innovative treatment methods need to be implemented even if that involves injecting the world’s deadliest organism into one’s body.

Leave a comment